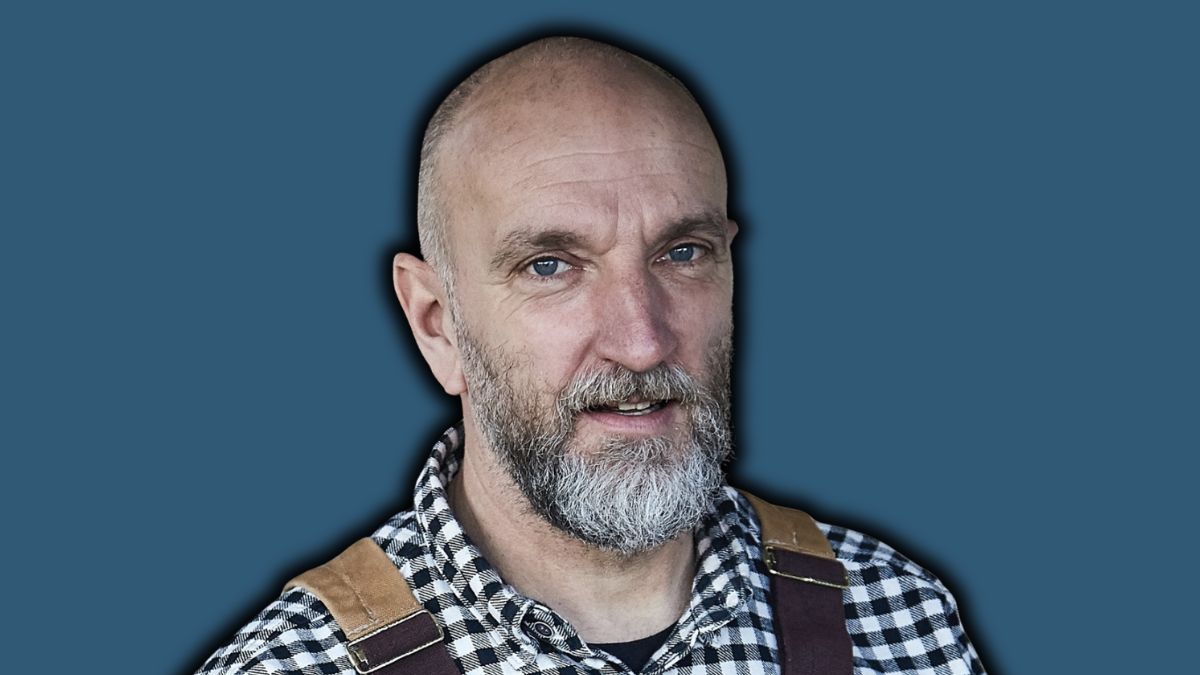

Andrew Ziminski: The Living Voice of Britain’s Stone, Churches, and Craft Heritage

Andrew Ziminski stands among the most respected contemporary interpreters of Britain’s built heritage. Known for his lifelong dedication to stonemasonry and church conservation, he bridges the gap between physical craft and intellectual history. His work does not simply preserve ancient buildings; it revives the stories embedded within stone, lime, and timber. Through decades of hands-on experience, thoughtful observation, and accessible writing, Andrew Ziminski has become a trusted guide to understanding how Britain was built and why its historic churches still matter today.

Early Life and Path into Stonemasonry

Andrew Ziminski’s journey into stonemasonry was not driven by fashion or nostalgia but by a genuine pull towards physical work and historical curiosity. Drawn to the tactile satisfaction of shaping stone, he trained in traditional masonry techniques at a time when many such skills were already under threat. From the outset, his interest extended beyond learning how to cut stone; he wanted to understand why buildings were made the way they were and how generations before him solved structural and aesthetic problems.

This early grounding in practical craftsmanship shaped his worldview. Stone, to Ziminski, is not merely a material but a language. Every tool mark, joint, and repair tells a story about the people who built, altered, or cared for a structure. This sensitivity to detail would later define both his conservation work and his writing.

A Career Rooted in Britain’s Historic Churches

Over several decades, Andrew Ziminski has worked extensively on historic churches and ecclesiastical buildings across England, particularly in the West Country. These buildings, ranging from modest parish churches to monumental cathedrals, form one of the richest architectural landscapes in Europe. Ziminski’s role has often involved repairing decayed stone, stabilising structures, and ensuring that interventions respect the original fabric of the building.

His work has taken him onto scaffolds high above nave floors, into crypts, and along weathered churchyards. Such long exposure has given him a rare, ground-level understanding of how churches function as buildings and as community spaces. He has seen how centuries of worship, weather, neglect, and renewal leave visible traces on stonework.

Crucially, Ziminski approaches conservation with humility. He does not aim to make old buildings look new. Instead, he seeks to maintain their integrity, acknowledging age and wear as part of their meaning. This philosophy aligns with the best traditions of British conservation practice, which value minimal intervention and historical honesty.

Understanding Stone as Historical Evidence

One of Andrew Ziminski’s most significant contributions lies in his ability to read stone as historical evidence. Where others might see erosion or damage, he sees timelines. Differences in tooling styles, mortar composition, and stone sourcing reveal phases of construction and repair. A blocked doorway or reused carving can point to changing liturgical practices or economic conditions.

This analytical skill is grounded in years of observation rather than abstract theory. Ziminski often emphasises that many historical truths are literally visible if one knows how to look. His work encourages a more attentive relationship with buildings, urging visitors and caretakers alike to slow down and notice.

Such insights have proven invaluable not only to fellow craftspeople but also to historians, architects, and clergy responsible for managing historic churches. By translating specialist knowledge into clear explanations, Ziminski helps ensure that decisions about repair and maintenance are informed by understanding rather than guesswork.

Writing as an Extension of Craft

Andrew Ziminski’s transition into authorship did not represent a departure from stonemasonry but an extension of it. His writing carries the same clarity, patience, and respect for material as his physical work. Rather than producing dry academic texts, he writes in a style that is reflective, grounded, and accessible to general readers.

His books draw upon personal experience, historical research, and close observation. They explore how Britain’s buildings were made, how they have changed, and what they reveal about the societies that produced them. Importantly, Ziminski avoids romanticising the past. He acknowledges hardship, imperfection, and compromise, presenting history as a complex human process rather than a polished narrative.

This approach has earned him praise for making architectural and ecclesiastical history engaging without oversimplification. His work appeals to readers interested in history, craft, religion, and the built environment, offering depth without exclusion.

Interpreting Churches Beyond Architecture

For Andrew Ziminski, churches are far more than architectural specimens. They are layered cultural artefacts that reflect belief, power, local identity, and continuity. His writing often explores elements that casual visitors overlook: fonts worn smooth by centuries of baptisms, floors reshaped by burials, and walls bearing faint traces of medieval paint.

By drawing attention to these features, Ziminski reframes how people experience churches. He encourages readers to see them not as silent monuments but as active participants in history. Even churches no longer used for regular worship retain meaning as repositories of memory and craft.

This broader interpretation is particularly relevant at a time when many churches face uncertain futures. Ziminski’s work implicitly argues for their value, not solely as religious spaces but as irreplaceable records of communal life.

Teaching and Public Engagement

Beyond writing and practical conservation, Andrew Ziminski is also known for his role as an educator and public speaker. Through talks, guided visits, and festival appearances, he shares his knowledge with diverse audiences. His manner is neither lecturing nor sentimental; instead, he invites curiosity and conversation.

What distinguishes his public engagement is its grounding in experience. He speaks as someone who has physically worked on the buildings he discusses. This lends authority without arrogance and allows him to answer questions with real examples rather than abstract theory.

Such engagement has helped demystify conservation work, making it more understandable and appreciated by the public. In doing so, Ziminski contributes to a broader culture of care for historic places.

Craft, Time, and Responsibility

A recurring theme in Andrew Ziminski’s thinking is responsibility across time. He often reflects on the idea that stonemasons work within a continuum, inheriting buildings from previous generations and passing them on to the next. Every intervention becomes part of that long story.

This perspective fosters restraint. Rather than imposing modern preferences, Ziminski advocates for listening to the building itself. What materials does it use? How has it behaved over centuries? What repairs have succeeded or failed? Such questions guide thoughtful conservation.

In a broader sense, his work raises ethical considerations about how society values skilled manual labour. Stonemasonry, like many traditional crafts, requires years of training and experience. By highlighting its intellectual and cultural dimensions, Ziminski challenges the false divide between manual and academic knowledge.

Influence on Heritage Thinking in Britain

While Andrew Ziminski may not be a household name in popular culture, his influence within heritage circles is significant. His ideas resonate with professionals and volunteers responsible for caring for historic buildings. He provides a model of how deep practical knowledge can inform interpretation, policy, and public understanding.

His writing has also influenced how non-specialists engage with churches. Readers often report that after encountering his work, they notice details they once ignored. This shift in perception represents a meaningful contribution, fostering appreciation that can translate into support for preservation.

At a time when funding pressures and changing demographics threaten many historic sites, such appreciation is vital. Ziminski’s calm, evidence-based advocacy offers an alternative to alarmism, grounded in respect for both past and present.

Andrew Ziminski in the Modern Cultural Landscape

In contemporary Britain, conversations about heritage can become polarised, framed as either nostalgia or obstruction to progress. Andrew Ziminski occupies a more nuanced position. He does not argue against change but insists that change should be informed by understanding.

His work fits within a growing interest in craft, sustainability, and place-based identity. Traditional building techniques often align with environmental principles, using local materials and repair rather than replacement. Ziminski’s emphasis on maintenance over demolition speaks directly to modern concerns about waste and resilience.

In this sense, his perspective feels increasingly relevant. By looking carefully at the past, he offers practical lessons for the future.

Conclusion

Andrew Ziminski represents a rare and valuable combination of skilled craftsperson, thoughtful observer, and clear communicator. Through decades of stonemasonry and conservation work, he has developed an intimate understanding of Britain’s historic churches and the stones from which they are built. Through his writing and public engagement, he has shared that understanding with a wide audience, enriching how people see and value their built environment.

His contribution lies not in grand gestures but in sustained attention: to materials, to history, and to responsibility across generations. In giving voice to stone, Andrew Ziminski helps ensure that Britain’s architectural heritage remains not only preserved, but understood.